Tutankhamun (/ˌtuːtənkɑːˈmuːn/, Ancient Egyptian: twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen (c. 1342 – c. 1325 BC), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the 18th dynasty (ruled c. 1334 – 1325 BC in the conventional chronology) during the New Kingdom of Egyptian history. His father was the pharaoh Akhenaten, believed to be the mummy found in the tomb KV55. His mother is his father’s sister, identified through DNA testing as an unknown mummy referred to as “The Younger Lady” who was found in KV35.

Tutankhamun took the throne at eight or nine years of age under the unprecedented viziership of his eventual successor, Ay, to whom he may have been related. He married his half sister Ankhesenamun. During their marriage they lost two daughters, one at 5–6 months of pregnancy and the other shortly after birth at full-term. His names—Tutankhaten and Tutankhamun—are thought to mean “Living image of Aten” and “Living image of Amun”, with Aten replaced by Amun after Akhenaten’s death. A small number of Egyptologists, including Battiscombe Gunn, believe the translation may be incorrect and closer to “The-life-of-Aten-is-pleasing” or, as Professor Gerhard Fecht believes, reads as “One-perfect-of-life-is-Aten”.

Tutankhamun restored the Ancient Egyptian religion after its dissolution by his father, enriched and endowed the priestly orders of two important cults and began restoring old monuments damaged during the previous Amarna period. He moved his father’s remains to the Valley of the Kings as well as moving the capitol from Akhetaten to Thebes. Tutankhamun was physically disabled with a deformity of his left foot along with bone necrosis that required the use of a cane, several of which were found in his tomb as well as body armor and bows—he had been trained in archery. He had other health issues including scoliosis and had contracted several strains of malaria.

Because Tutankhaten was just nine years old when he assumed power in 1332 B.C.E., the first years of his reign were probably controlled by an elder known as Ay, who bore the title of Vizier.

Ay was assisted by Horemheb, Egypt’s top military commander at the time. Both men reversed Akhenaten’s decree to worship Aten in favor of the traditional polytheistic beliefs.

King Tut had the royal court moved back to Thebes. He sought to restore the old order, hoping that the gods would once again look favorably on Egypt. He ordered the repair of the holy sites and continued construction at the temple of Karnak. He also oversaw the completion of the red granite lions at Soleb.

While foreign policy was neglected during Akhenaten’s reign, Tutankhamun sought to restore better relations with Egypt’s neighbors. While there is some evidence to suggest that Tutankhamun’s diplomacy was successful, during his reign battles took place between Egypt and the Nubians and Asiatics over territory and control of trade routes.

Tutankhamun was trained in the military, and there is some evidence that he was good at archery. However, it is unlikely that he saw any military action.

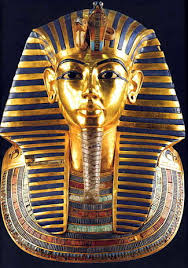

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter of Tutankhamun’s nearly intact tomb, in excavations funded by Lord Carnarvon,received worldwide press coverage. With over 5,000 artifacts, it sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun’s mask, now in the Egyptian Museum, remains a popular symbol. The deaths of a few involved in the discovery of Tutankhamun’s mummy have been popularly attributed to the curse of the pharaohs. He has, since the discovery of his intact tomb, been referred to colloquially as “King Tut”.

Some of his treasure has traveled worldwide with unprecedented response. The Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities allowed tours beginning in 1962 with the exhibit at the Louvre in Paris, followed by the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art in Tokyo, Japan. The exhibits drew in millions of visitors. The 1972–1979 exhibit was shown in United States, Soviet Union, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. There were no international exhibitions again until 2005–2011. This exhibit featured Tutankhamun’s predecessors from the 18th dynasty, including Hatshepsut and Akhenaten, but did not include the golden death mask. The treasures 2019–2022 tour began in Los Angeles and will end in 2022 at the new Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo, which, for the first time, will be displaying the full Tutankhamun collection, gathered from all of Egypt’s museums and storerooms.

Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten (originally named Amenhotep IV[10]) who is believed to be the mummy found in tomb KV55. His mother is one of Akhenaten’s sisters. At birth he was named Tutankhaten, a name reflecting the Atenist beliefs of his father. His wet nurse was a woman called Maia, known from her tomb at Saqqara

While some suggestions have been made that Tutankhamun’s mother was Meketaten, (the second daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti) based on a relief from the Royal Tomb at Amarna,[a] given that she was about 10 years old at the time of her death, this has been deemed unlikely.[16] Another interpretation of the relief names Nefertiti as his mother.

In 2008 genetic analysis was carried out on the mummified remains of Tutankhamun and others thought or known to be New Kingdom royalty by a team from University of Cairo. The results indicated that his father was the KV55 mummy, identified as Akhenaten, and that his mother was the KV35 Younger Lady, who was found to be a full sister of her husband.This means that the KV35 Younger Lady cannot be identified as Nefertiti as she was not known to be a sister of Akhenaten.The team reported it was over 99.99 percent certain that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.The validity and reliability of the genetic data from mummified remains has been questioned due to possible degradation due to decay. Researchers such as Marc Gabolde and Aidan Dodson claim that Nefertiti was indeed Tutankhamun’s mother. In this interpretation of the DNA results the genetic closeness is not due to a brother-sister pairing but the result of three generations of first cousin marriage, making Nefertiti a first cousin of Akhenaten.

When Tutankhamun became king, he married his half-sister, Ankhesenpaaten, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun.They had two daughters, neither of whom survived infancy.While only an incomplete genetic profile was obtained from the two mummified foetuses, it was enough to confirm that Tutankhamun was their father. Likewise, only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21 has been obtained so far. KV21A has been suggested as the mother of the foetuses but the data is not statistically significant enough to allow her to be securely identified as Ankhesenamun. Computed tomography studies published in 2011 revealed that one daughter was born prematurely at 5–6 months of pregnancy and the other at full-term, 9 months. Tutankhamun’s death marked the end of the royal line of the 18th dynasty.

Once crowned and after “Taking council” with the god Amun, Tutankhamun made several endowments that enriched and added to the priestly numbers of the cults of Amun and Ptah. He commissioned new statues of the deities from the best metals and stone and had new processional barques made of the finest cedar from Lebanon and had them embellished with gold and silver. The priests and all of the attending dancers, singers and attendants had their positions restored and a decree of royal protection granted to insure their future stability.

Tutankhamun’s second year as pharaoh began the return to the old Egyptian order. Both he and his queen removed ‘Aten’ from their names, replacing it with Amun and moved the capital from Akhetaten to Thebes. He renounced the god Aten, relegating it to obscurity and returned Egyptian religion to its polytheistic form. His first act as a pharaoh was to remove his father’s mummy from his tomb at Akhetaten and rebury it in the Valley of the Kings. This helped strengthen his reign. Tutankhamun rebuilt the stelae, shrines and buildings at Karnak. He added works to Luxor as well as beginning the restoration of other temples throughout Egypt that were pillaged by Akhenaten.

Tutankhamun’s artifacts have traveled the world with unprecedented visitorship. The exhibitions began in 1962 when Algeria won its independence from France. With the ending of that conflict, the Louvre Museum in Paris was quickly able to arrange an exhibition of Tutankhamun’s treasures through Christiane Desroches Noblecourt. The French Egyptologist was already in Egypt as part of a UNESCO appointment. The French exhibit drew 1.2 million visitors. Noblecourt had also convinced the Egyptian Minister of Culture to allow British photographer George Rainbird to re-photograph the collection in color. The new color photos as well as the Louvre exhibition began a Tutankhamun revival.

In 1965 the Tutankhamun exhibit traveled to Tokyo, Japan where it garnered more visitors than the future New York exhibit in 1979. The exhibit was held at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art with almost 1.75 million visitors. The blockbuster attraction exceeded all other exhibitions of Tutankhamun’s treasures for the next 60 years. The Treasures of Tutankhamun tour ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum from 30 March until 30 September 1972. More than 1.6 million visitors saw the exhibition. The exhibition moved on to many other countries, including the United States, Soviet Union, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the U.S. exhibition, which ran from 17 November 1976 through 15 April 1979. More than eight million attended.

In 2005, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society, launched a tour of Tutankhamun treasures and other 18th Dynasty funerary objects, this time called Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. It featured the same exhibits as Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter in a slightly different format. It was expected to draw more than three million people but exceeded that with almost four million people attending just the first four tour stops.The exhibition started in Los Angeles, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Chicago, Philadelphia and London before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. An encore of the exhibition in the United States ran at the Dallas Museum of Art.After Dallas the exhibition moved to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, followed by the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.

Tutankhamun exhibition in 2018

The exhibition visited Australia for the first time, opening at the Melbourne Museum for its only Australian stop before Egypt’s treasures returned to Cairo in December 2011.

The exhibition included 80 exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun’s immediate predecessors in the 18th dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun’s burial artifacts, as well as 50 from Tutankhamun’s tomb. The exhibition did not include the gold mask that was a feature of the 1972–1979 tour, as the Egyptian government has decided that damage which occurred to previous artifacts on tours precludes this one from joining them.

In 2018 it was announced that the largest collection of Tutankhamun artifacts, amounting to forty percent of the entire collection, would be leaving Egypt again in 2019 for an international tour entitled; “King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh”. The 2019-2022 tour began with an exhibit called; “Tutankhamun, Pharaoh’s Treasures,” which launched in Los Angeles and then traveled to Paris. The exhibit featured at the Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris ran from March to September 2019. The exhibit featured one hundred and fifty gold coins, along with various pieces of jewelry, sculpture and carvings, as well as the renowned gold mask of Tutankhamun. Promotion of the exhibit filled the streets of Paris with posters of the event. The full international tour ends with the opening of the new Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo where the treasures will be permanently housed.